A PROFILE OF A SUBMARINE POW VETERAN:

ROBERT W. LENTS

By Art Randall

NOTE: Robert "Bob" W. Lents is a Life Member of the US SubVets of WWII, SubVets Inc. and a Plank

owner of the Twin Lakes Base, Mountain Home Arkansas, where he lives with Carolyn, his wife of 58

years. He is a Japanese POW Survivor! This Profile deals with his last patrol, his capture and internment as a

Prisoner of War. He is also a Charter Member of the US Submarine Veterans POW Survivors Association.

Appeared in the American Submariner Issue 2005-01, pages 12 & 13

Reprinted with permission of the American Submariner Editor

*.

Robert W. Lents, circa 1941

USS Perch (SS 176)

(Left-click picture to enlarge)

During the last part of 1940, Bob was assigned to the USS Seawolf (SS197) stationed in Manila. He

served on her for some seven months and completed his qualifications. He was then transferred to USS

Perch (SS 176). Sadly, as the events of WWII were to unfold, four years later, on 3 October 1944 and on

her 15th War Patrol, Seawolf was lost along with 102 of her crew. Many of her crew were friends of Bob

from his days aboard.

When the war began," Bob recalled, "we were in the Cavite Navy Yard. I will never forget the morning of

December 8,1941, as Manila's newspaper's headlines declared in large bold letters, 'PEARL HARBOR

BOMBED.' The hairs on the back of my neck stood up as if an icy chill had swept over me. "We are at war,

I thought."

World War II came to Manila in a fiery reign of terror. At the Cavite Navy Yard, some 40 Japanese

warplanes strafed and bombed, again and again. "The USS Sea Lion was in the Cavite Yard being

overhauled when the heavy force of Japanese bombers raided it. She was so badly damaged she had to

be blown up."

The raids were so large, frequent and swift that the Cavite Navy Yard was all but totally destroyed. "That

first raid left more than 700 Navy and civilians dead. We were taking on stores at the time and had to run

out in the bay to dive, which resulted in the loss of half our food." Bob remembers, "The Perch went on

patrol that night, 10 December 1941, along the West Coast of the Philippines and patrolled by a Japanese

Navy Base on Formosa. We fired some torpedoes at one ship but got no hits as one of the fish made a

circular run and exploded off our side. We realized something was wrong with the torpedoes but had no

way to know what the problem was."

Bob also recalled the first War Patrol for both him and Perch. "We received a report about a 5,600-ton

supply ship out of Hong Kong accompanied by two destroyers and a cruiser. Running at top speed, we

sighted it and made a daring daylight attack. We sank the supply ship and then dove hoping to set up an

attack on the cruiser; then the depth charge attack began.

"While the destroyers pounded away, the cruiser launched a plane and dropped a bomb on us. While

all this was going on, the cable that held the periscope broke and the scope fell to the bottom of the well.

Low on food and fuel, we were happily ordered to Darwin, Australia, for repairs, arriving late January

1942.

Following repairs and with the boat reprovisioned, we got underway on 3 February 1942 with LCDR R. A.

Hurt Commanding. We were bound for the Java Sea for what would be my and the Perch's second and

last Patrol.

"From 8 to 23 February, Perch received several reports concerning enemy concentrations near her area

and was directed to patrol or perform reconnaissance in various positions near the islands in the Java Sea.

On 25 February she reported two previous attacks stating she had received a shell hit on her conning

tower which damaged the antenna, making transmissions uncertain although she could still receive."

On 27 February, Perch sent a contact report on two cruisers and three destroyers. No further reports were

received from her and she failed to arrive in Fremantle where she had been ordered. The last station

assignment was given Perch on 28 February 1942, in the Java Sea.

A large enemy convoy had been cruising about, waiting to land on Java. Perch discovered their objective

and waited for an opportunity to report it. Shortly after surfacing on the night of 1 March, Perch sighted

two destroyers and submerged to avoid detection.

The destroyers passed by Perch but soon returned, one very near. LCDR Hurt prepared for a torpedo

attack but at 800 to 1000 yards a destroyer turned straight toward them. Realizing they had been

spotted, Hurt ordered 180 feet. At 90 to 100 feet, the destroyer passed over and dropped a string of

depth charges. Perch struck the bottom at 147 feet.

During the attacks that followed, Perch lost power on her port screw, but managed to pull clear of the

bottom, surfacing when the depth charging ceased. Shortly before dawn two Japanese destroyers were

sighted and once more Perch went to the bottom, this time at 200 feet. Initial efforts to move her from

the bottom were unsuccessful.

The attacks continued until after daylight. After hours of effort, at dusk on 2 March, Perch surfaced,

finding no enemy in sight. Her reduction gears were in bad shape, there were serious electrical grounds,

broken battery jars and the engine room hatch leaked badly. As a result plans were made to scuttle the

Perch if necessary.

On 3 March 1942 Perch attempted to dive before daylight but it was soon discovered that the damages

suffered during the attacks of the previous day had made it impossible to do so. Water poured in from

conning tower and engine room hatches, three-inch circulating water lines and leaks in the hull. While the

crew frantically worked to resolve these problems, three enemy destroyers came into view and opened

fire.

Perch's gun was inoperative and torpedoes could not be fired. Enemy depth charges had caused three

torpedoes to run in their tubes. With no way to resist, the decision was made to abandon ship and scuttle

her. The entire crew got into the water safely and soon the Japanese ships picked them up.

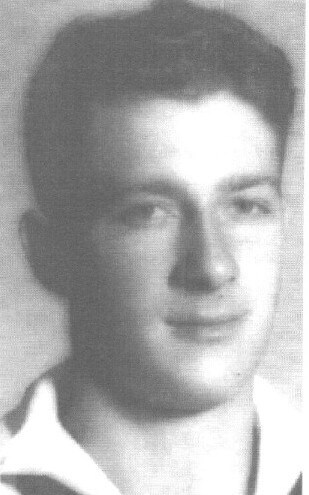

Perch crew on deck of Japanese destroyer.

Photo was found in the radio room of a Japanese Submarine in Japan after the war in 1945.

(Left-click picture to enlarge)

"The crew of 60 was taken first to the Makkassar POW camp, then the officers and radiomen were taken

to Japan. In October 1942, 200 English, Dutch and Americans were taken to Ofuna, Japan, including some

of the Perch crew, where they were interrogated. Later they were sent to the Ashio copper mines, where

they were forced to work until the end of the war."

In a post-war investigation of the Makkassar prisoner-of-war camp, a report was made to the US Navy

Department by an Officer from the Destroyer USS Pope, a POW at the Makkassar camp. He reported

Japanese treatment of the POW's was brutal, humiliating and degrading. Punishment was extreme and

cruel, as POW's were constantly subjected to heavy beatings, without reason. Arms and legs were broken,

and teeth knocked out. Even more brutal treatment, outlawed by civilized nations, was routinely exacted

against the prisoners.

"On May 1, 1944, all Americans in the camp were beaten up to seventy-five times across the buttocks

with baseball bat-sized clubs. From this date, the health of Americans deteriorated steadily and survival

became questionable. In June 1944 they were moved to a camp in a swampy, malaria-infested area, with

poor sanitary conditions. This caused untold illnesses that went untreated. Water was dangerous to drink

and insufficient in supply causing many other life-threatening diseases which crippled both the mind and

body. As the number of weakened POW's increased and their conditions worsened, the Japanese guards

and others ridiculed and otherwise humiliated the helpless prisoners.

"In August 1944 allied bombing became quite heavy. In retaliation, conditions for the prisoners

deteriorated and reached new life-threatening lows. The food was poor and insufficient to sustain men

forced to labor in the copper mines.

"Now, because of the bombing, food was maliciously reduced again, causing rampantly severe

malnutrition, diseases and other maladies. Many POW's, frail, with skeleton-like bodies, gave up the

struggle. The peace afforded by death became more appealing than life. Many of them, stricken with

malaria, died without medical treatment. Those who cherished life labored on and somehow survived.

"On July 26, I, along with 200 other POWs, was transferred to Japan's POW camp at Batavia, Java. The

trip was made under the worst possible conditions on the topside of a small oil tanker with 200 Jap army

personnel. We were forced to remain in a sitting position under the grueling tropical sun for three days

with less than a half pint of water, supplemented by two or three biscuits and two spoonfuls of sugar. On

Java, a two-day train trip under very crowded conditions brought us to Batavia.

"Finally, in August 1945, we were released from isolation barracks to the main camp and five days later

we were notified of the end of the war. On September 18, 1945 -- after three and 1/2 years as a

Japanese POW -- I was liberated in Java and flown to Calcutta, India, to the US Army Hospital; and then

to the Naval Hospital at St. Albans, Long Island, N.Y. After being released from the hospital I was sent

home on a 90 day leave.

"l was married on February 1,1946. I was then assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center. On

December 30, 1946, I received a medical discharge because of an injury received during the loss of Perch.

After discharge I returned to Iowa and took a Civil Service examination resulting in my being employed by

the USPS. I soon became Postmaster in my hometown. Later I transferred to become a rural mail carrier.

I retired in 1976 moving to Arkansas where Carolyn and I now reside."

Bob summarizes his POW experience as follows: "There is no way to relate what being a prisoner of war

can do to the mind, body and spirit -- even if confined under the most humane conditions demanded by

the Geneva Convention and rules of war.

"Not hearing from home, not knowing whether your country still exists as a sovereign nation; not knowing

the fate of your loved ones, shipmates, family, or whether you will see the sun rise in the morning or set

tomorrow afternoon, wears at the human spirit. It remains with you in the dark corners of your mind for

the rest of your life, coming to the fore when you least expect it. You relive it all over again, sometime in

a flashback that lasts for only a moment.

"No POW who lived under the terrible conditions we of the Perch and our camp mates experienced, can

ever say the horrors of those years have not left a permanent scar upon them. Those scars will always be

with us; the visions of death all about us.

"Thoughts of shipmates dying, knowing you can do nothing for them but to hold them in your arms, tears

streaming down your cheeks, as they die, all you can do is rock back and forth in abject anguish, knowing

they will soon be gone, trying to give them but a moment of comfort. One cannot keep from wondering

the rest of their life: 'why was it I who survived? Why was I not among the thousands that did not make

it, those who still remain on eternal patrol?' I know in my heart and mind we will all meet again someday,

yet even then I will still wonder why I was one of those spared and not among those that perished!"

Fifty-two of the Perch crew were received from the Japanese at war's end and eight died as POW's. Perch

was credited with sinking a 5600-ton enemy freighter on her first patrol, conducted west of the

Philippines.

Perch Crewmembers who died in captivity:

Atkeison, W.L. TM2

Brown, C.N. MM2

Dewes, R.J. PHAR

Edwards, N.E. CEM

Greco, J. TM3

McCreary, F.E. MM1

Newsome, A.K. CMMA

Wilson, R.A. FC1