Dec. 2, 1943

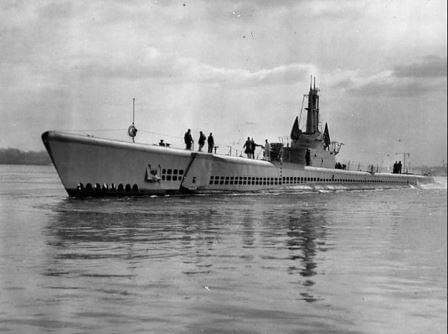

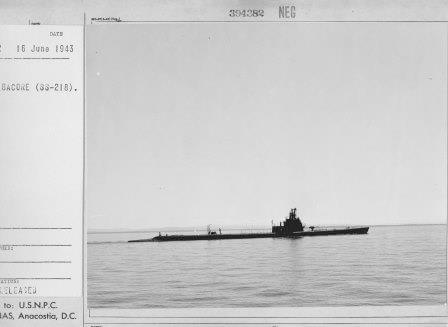

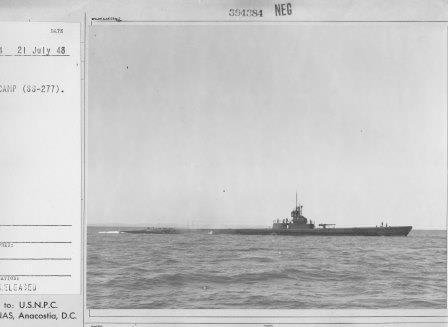

USS Capelin

(SS‑289)

76 men lost

Japanese records studied after the war listed an attack on a supposed United States submarine

on 23 November, off Kaoe Bay, Halmahera. Evidence of an actual contact was slight, and the

Japanese state that this attack was broken off. Enemy minefields are now known to have been

placed in various positions along the north coast of Sulawesi (Celebes) in Capelin's area,

and she may have been lost because of a mine explosion. Gone without a trace, with all her

crew, Capelin remains in the list of ships lost without a known cause.

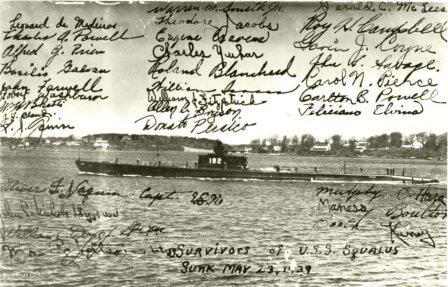

Greenleaf, D. T., CMoMM, Rhimann, R. C., LT(jg), and Smith, D. T., MoMM2 are often listed

on "Lost Submariners" memorials, and/or included in the figures that are given for

the lost boats. It is highly doubtful that these three men were on the boat's final patrol.

"Greenleaf, D. T." and "Smith, D. T." never appear in Capelin's muster

rolls (two other Smiths do, and are accounted for in our listings), and Rhimann has not been

found in any record. The original source of these three names is U.S. Submarine Losses -

World War II. Greenleaf, Rhimann, and D.T. Smith appear in the 1946 edition, were removed

in the 1949 edition, and Rhimann and D. T. Smith were re-entered in the 1963 edition. None

of these men are listed as lost in NARA, Navy Casualty, DPMO, ABMC, or the SubVets of WWII

documentation. It is believed that Greenleaf, Rhimann and D. T. Smith were not aboard the

vessel when she was lost, if ever.